The Mirror We Built

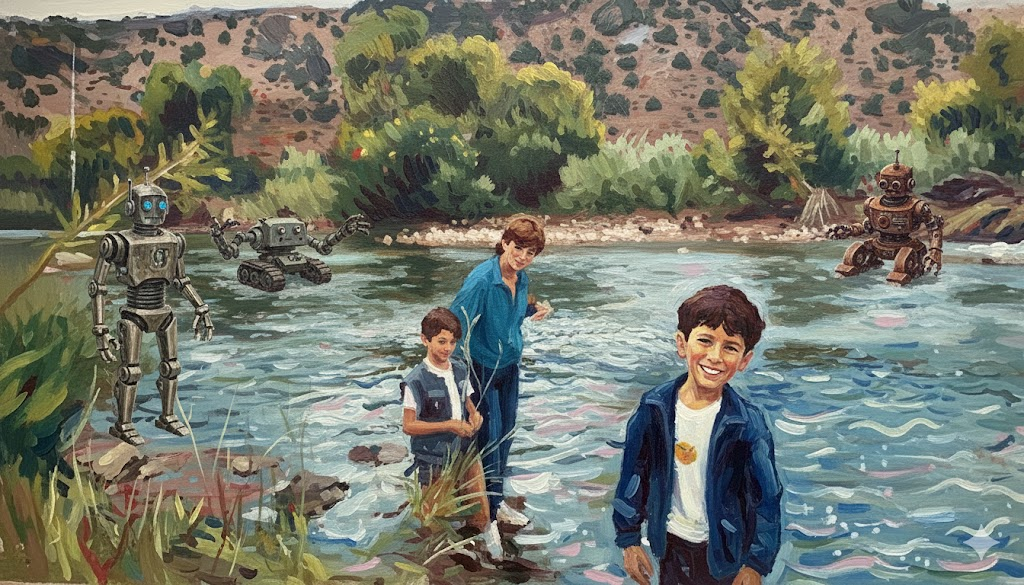

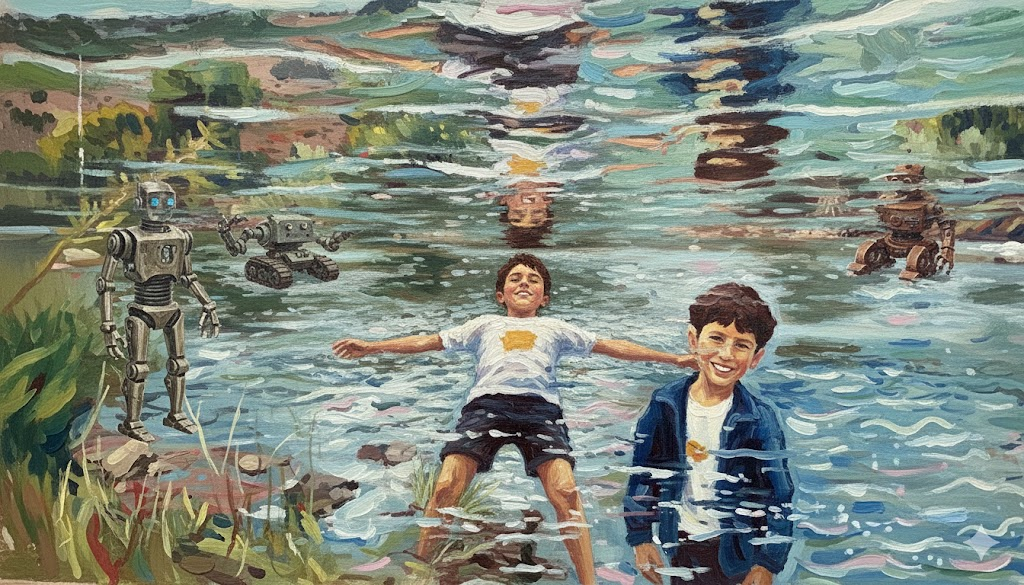

When I was a child, I tried to build an artificial intelligence. I had a Mac Plus and a book about C++, and I knew—with the certainty that only children have—that I could model a brain. The idea was simple: wires that became closer and more connected over time, strengthened by sensory input, shaped by feedback. Learning as proximity. Intelligence as accumulated connection.

I wasn't up to the task. I didn't have the math, the compute, or the conceptual vocabulary. What I had was the drive to make something that could think. I wanted to build a mind because building minds was something humans should be able to do.

Decades later, the thing I reached for exists. Not because I built it—I didn't—but because the drive I felt turned out to be shared. Millions of people pushed on the same problem, and now there are systems that complete your sentences, generate images from descriptions, write code, hold conversations. The shape I intuited as a child—learning through connection, intelligence as pattern—wasn't wrong. I just couldn't execute it alone.

There's something strange about watching your childhood dream materialize through collective effort. It's not satisfaction exactly. It's more like recognition. The drives that built this thing are mine. They're also everyone's.

Most discourse about AI falls into predictable camps. The optimists promise transformation: disease cured, poverty solved, creativity amplified. The pessimists warn of displacement, manipulation, existential risk. The moderates insist it's "just a tool," as if that settles anything.

All three positions share something in common: they treat us as witnesses. Something is happening to us. We watch, predict, worry, hope. The future arrives and we react.

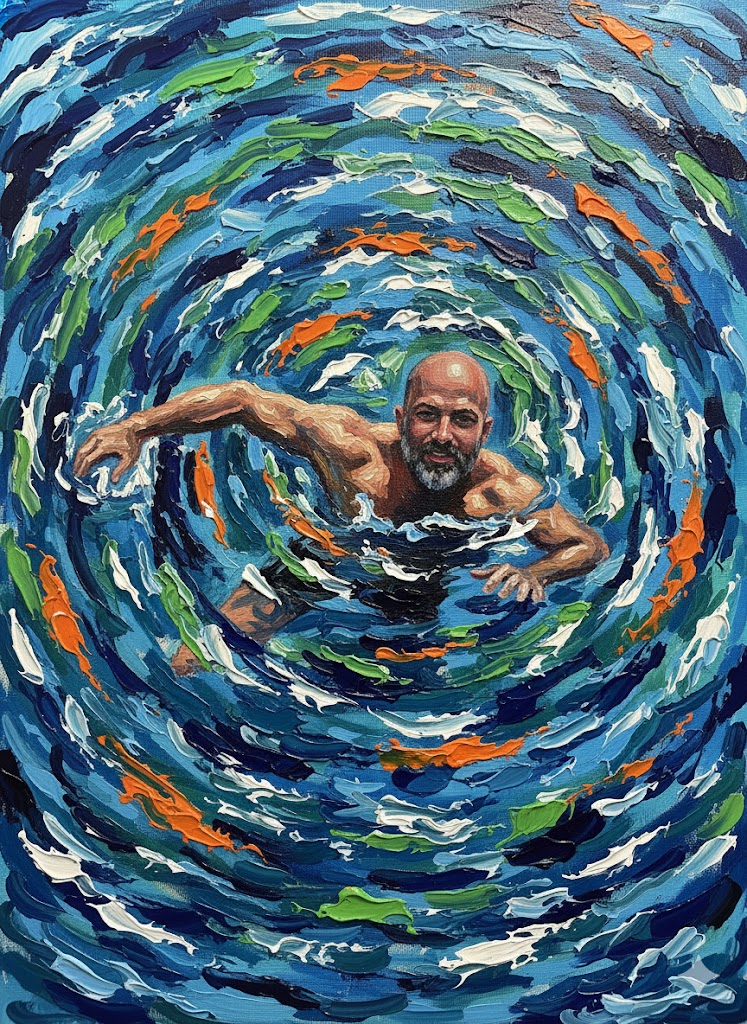

But this framing is wrong—or at least incomplete. We're not observers of AI's development. The drives that built it are human drives. The will to know without limit. The will to create. The will to transcend biological constraints. The will, if we're honest, to be relieved of burden. AI is not an alien visitation. It's a mirror.

And mirrors show you things you might prefer not to see.

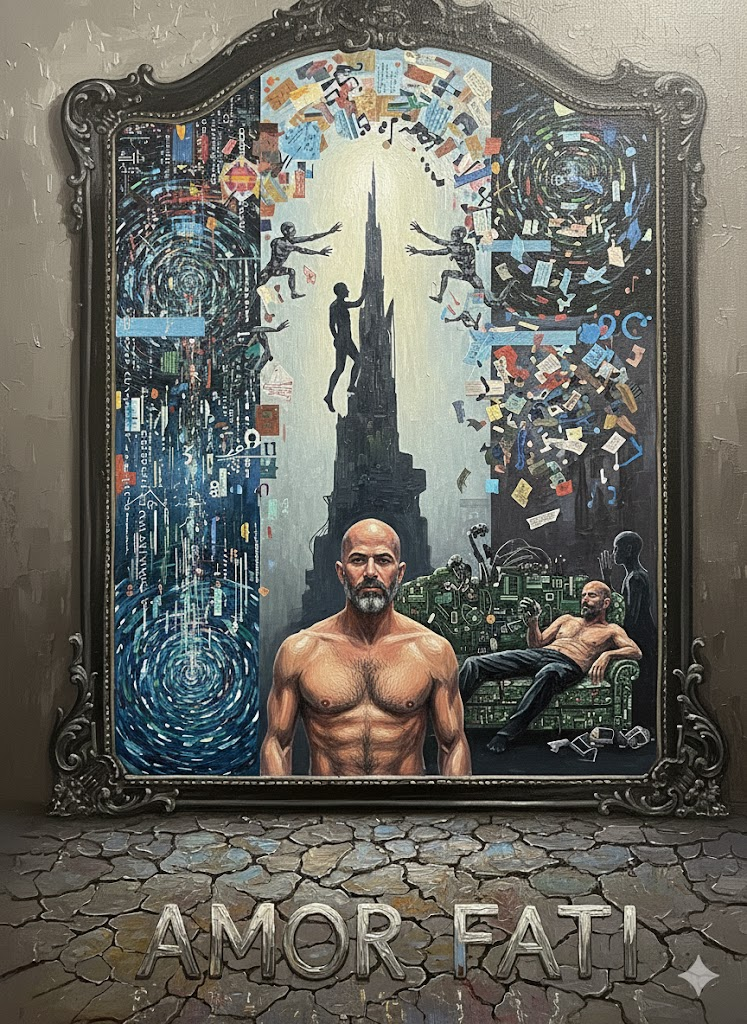

Friedrich Nietzsche had a concept he called amor fati—love of fate. It appears in The Gay Science: "I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who makes things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth."

This is often confused with Stoic acceptance—tolerating what you cannot change, enduring what must be endured. But Nietzsche meant something stranger and more demanding. He wasn't describing resignation. He was describing affirmation. Loving fate means willing your life exactly as it is, including the suffering, including what seems terrible, as if you had chosen every detail yourself.

In Ecce Homo, he put it starkly: "My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity."

This isn't optimism. Optimism says things will be fine. Amor fati says: I affirm this, all of it, regardless.

The test Nietzsche proposed was the thought experiment of eternal recurrence. If a demon told you this exact life would repeat infinitely, identical in every detail—every joy, every loss, every tedious afternoon—would you curse it or embrace it? The person who can say yes has achieved something. They've stopped resenting their existence. They've stopped wishing they were elsewhere.

What makes this active rather than passive is the creative stance it requires. You're not discovering meaning in fate. You're imposing meaning through your affirmation. The strong person doesn't say "I accept because I must." They say "I will this."

What does this have to do with artificial intelligence?

I think AI is the kind of transformation that demands we ask the eternal recurrence question. Not about AI specifically—would you will this technology to repeat forever?—but about the drives that produced it. Would you will humanity's relentless push toward more knowledge, more capability, more transcendence? Would you affirm the will to power that expresses itself in creation and discovery and, yes, in building systems that might surpass us?

Because you can't separate AI from those drives. They're the same thing. The mirror shows us that we built this because we are the kind of creatures who build things like this. The question is whether we can look at that reflection and say yes.

There are weaker and stronger versions of this affirmation.

The weakest version is resignation dressed up: "AI is coming whether we like it or not, so we might as well make peace with it." This is Stoicism, not amor fati. It accepts the inevitable while quietly resenting it.

A stronger version affirms the conditions that produced AI—human curiosity, the will to knowledge, the technological drive—as expressions of life seeking to overcome itself. You're not just tolerating the outcome. You're affirming the process that led here.

But the strongest version goes further. It says: I participate in shaping this transformation not despite uncertainty but through uncertainty. I create meaning in the midst of change rather than waiting for meaning to be revealed. I am not a witness. I am an author.

This is what amor fati demands. Not passive acceptance of AI's arrival, but active participation in what it becomes.

What the Mirror Shows

It shows our will to knowledge without limit. We built systems to know more, faster, beyond what any individual human could hold. But the reflection reveals that this drive has no natural stopping point. We didn't want enough knowledge. We wanted all of it. The mirror doesn't flatter us here; it shows an appetite, not wisdom.

It shows our will to create. Generative AI literalizes the creative impulse, then demonstrates that "creation" was never as mystical as we pretended. Much of what we called creativity turns out to be pattern and recombination. The painter, the writer, the composer—we're working with materials we didn't invent, combining them in ways that feel novel to us. AI makes this visible in a way that's hard to unsee.

It shows our will to transcend. The drive to exceed biological limits, to be more than what evolution made us. AI reflects this back as a question: you wanted to surpass the human—here's what "surpassing the human" actually looks like. Do you still want it?

And it shows our will to be relieved of burden. This is the shadow side. We built AI not just to amplify ourselves but to replace the parts of ourselves we find tedious. The mirror shows our exhaustion alongside our ambition. We want to think less, decide less, bear less responsibility. That's in the reflection too.

Amor fati means affirming all of this. Not just the flattering drives—creativity, transcendence, noble curiosity—but the exhaustion, the laziness, the appetite that doesn't know when to stop. You don't get to select which parts of the mirror to acknowledge.

The Secular Arc

There's a longer arc here that AI completes rather than begins.

Nietzsche announced the death of God in the late nineteenth century—not as theology but as cultural diagnosis. The structures that once guaranteed meaning, that provided stable foundations for truth and value, had eroded. Modernity would have to create meaning rather than discover it. The ground was gone.

The twentieth century extended this process. Knowledge became democratized, then commodified. Information that once required pilgrimage to libraries became searchable from anywhere. Expertise that once took decades to acquire became summarizable in blog posts. The sacred became accessible, which meant it became ordinary.

AI completes this arc. When knowledge is fully commodified—when anyone can summon any information instantly, when expertise can be simulated convincingly, when the barriers to knowing collapse entirely—knowledge stops being the locus of value. You can no longer hide behind credentials, access, or specialized training. The mirror shows everyone naked.

What remains when the last shelters fall? Nietzsche's answer: the capacity to create values, not merely to possess information. The secular age stripped God as guarantor of meaning. AI strips knowledge as guarantor of status. What's left is pure will to power—the ability to impose form on chaos, to create meaning from nothing, to affirm.

This is terrifying if you were relying on those shelters. It's liberating if you weren't.

What Counts as Participation?

I said the strongest form of amor fati involves active engagement, not just acceptance. But active engagement takes different forms.

Building is the highest. The person who creates AI systems participates in will to power most directly—imposing form on chaos, making something exist that didn't before. Builders can't hide behind "I just work here" or "the market demanded it." Amor fati for the builder means affirming what you build, including consequences you can't foresee. This is the weight Nietzsche places on creators: "That the creator may be, suffering is needed and much transformation."

But all genuine forms of affirmation work. Writing and criticism that shape how AI is understood—that's participation. Deliberate use of AI as extension of your own will, not replacement of it—that's participation. Even conscious refusal can be affirmation, if it's a creative act of self-definition rather than reaction from fear.

What doesn't count is drift. Using AI because it's there, because everyone else is, because it's easier than deciding not to—this is the last man with better tools. Nietzsche described the last man in Zarathustra as the comfortable nihilist who blinks and says "we have invented happiness." The last man consumes. He doesn't create. He doesn't affirm.

The difference between conscious refusal and passive adoption is everything. The former is still amor fati. The latter is its absence.

What This Demands

I should be honest about what this essay is not doing. It's not providing reassurance.

Amor fati is not a promise that things will be fine. The Stoic says: accept what you cannot change. The optimist says: it will work out. Amor fati says: I affirm this, including the parts that might destroy me.

Nietzsche affirmed suffering. He affirmed cruelty, tragedy, destruction—as part of life's totality. Applied to AI, this means affirming the whole process: displacement, chaos, the concentration of power, the epistemic vertigo, the possibility of catastrophe. You're not affirming a sanitized vision of AI helping humanity flourish. You're affirming the transformation in its full uncertainty.

This is uncomfortable. It should be. An affirmation that costs nothing isn't amor fati. It's just optimism with philosophical decoration.

The question the mirror poses isn't "will AI be good or bad?" It's "can you affirm the drives that built it—your drives, humanity's drives—knowing that you can't control what comes next?"

I still think about that Mac Plus, the C++ compiler, the conviction that I could model a brain with wires that grew closer over time. I was reaching for something I couldn't execute. Now the execution has happened, and I recognize the shape of what got built.

The drives that made me try are the same drives that made this technology exist. I didn't build it, but I was part of the collective will that did—the human need to know, to create, to transcend, to be relieved of burden. The mirror shows me that. It doesn't ask if I approve. It asks if I affirm.

I'm still working on the answer.

But I know this much: watching from the sidelines isn't affirmation. Commentary isn't participation. The only way through is to engage—to build, to shape, to use deliberately, or to refuse deliberately. To author your relationship to the transformation rather than waiting for someone else to tell you what it means.

The mirror is here. What looks back is not what you hoped. It's what you are.

The question is whether you can love it anyway.